MDD

01 where/04 Tan Binh/Z inactive/Dai Trinh

| x |

|

Jul 16 (2 days ago)

| |||

| ||||

Major depressive disorder

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other depressive disorders, see Mood disorder.

| Major depressive disorder | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| |

| ICD-10 | F32, F33 |

| ICD-9 | 296.2, 296.3 |

| OMIM | 608516 |

| DiseasesDB | 3589 |

| MedlinePlus | 003213 |

| eMedicine | med/532 |

| MeSH | D003865 |

Major depressive disorder (MDD) (also known as clinical depression, major depression, unipolar depression, or unipolar disorder; or as recurrent depression in the case of repeated episodes) is a mental disorder characterized by a pervasive and persistent low mood that is accompanied by low self-esteem and by a loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. This cluster of symptoms (syndrome) was named, described and classified as one of the mood disorders in the 1980 edition of theAmerican Psychiatric Association's diagnostic manual.

The term "depression" is used in a number of different ways. It is

often used to mean this syndrome but may refer to other mood disorders

or simple to a low mood. Major depressive disorder is a disabling

condition that adversely affects a person's family, work or school life,

sleeping and eating habits, and general health. In the United States,

around 3.4% of people with major depression commitsuicide, and up to 60% of people who commit suicide had depression or another mood disorder.[1]

The diagnosis of major

depressive disorder is based on the patient's self-reported experiences,

behavior reported by relatives or friends, and a mental status examination.

There is no laboratory test for major depression, although physicians

generally request tests for physical conditions that may cause similar

symptoms. The most common time of onset is between the ages of 20 and 30

years, with a later peak between 30 and 40 years.[2]

Typically, people are treated with antidepressant medication

The understanding of the

nature and causes of depression has evolved over the centuries, though

this understanding is incomplete and has left many aspects of depression

as the subject of discussion and research. Proposed causes include psychological, psycho-social, hereditary, evo

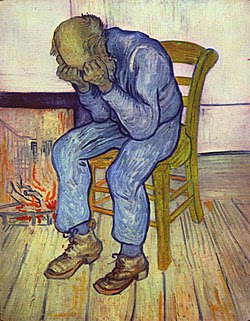

Symptoms and signs

Major

depression significantly affects a person's family and personal

relationships, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and

general health.[6] Its impact on functioning and well-being has been compared to that of chronic medical conditions such as diabetes.[7]

A person having a major depressive episode usually exhibits a very low mood, which pervades all aspects of life, and an inability to experience pleasure in activities that were formerly enjoyed. Depressed people may be preoccupied with, or ruminate over, thoughts and feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt or regret, helplessness, hopelessness, and self-hatred.[8] In severe cases, depressed people may have symptoms ofpsychosis. These symptoms include delusions or, less commonly, hallucinations, usually unpleasant.[9] Other symptoms of depression include poor concentration and memory (especially in those with melancholic or psychotic features),[10] withdrawal from social situations and activities, reduced sex drive, and thoughts of death or suicide. Insomnia is common among the depressed. In the typical pattern, a person wakes very early and cannot get back to sleep.[11] Insomnia affects at least 80% of depressed people.[medical citation needed]Hypersomnia, or oversleeping, can also happen.[11] Some antidepressants may also cause insomnia due to their stimulating effect.[12]

A depressed person may

report multiple physical symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, or

digestive problems; physical complaints are the most common presenting

problem in developing countries, according to the World Health Organization's criteria for depression.[13] Appetite often decreases, with resulting weight loss, although increased appetite and weight gain occasionally occur.[8] Family and friends may notice that the person's behavior is either agitated or lethargic.[

Depressed children may often display an irritable mood rather than a depressed mood,[8] and show varying symptoms depending on age and situation.[16] Most

lose interest in school and show a decline in academic performance.

They may be described as clingy, demanding, dependent, or insecure.[11] Diagnosis may be delayed or missed when symptoms are interpreted as normal moodiness.[8] Depression may also coexist with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), complicating the diagnosis and treatment of both.[17]

Comorbidity

Major depression frequently co-occurs with other psychiatric problems. The 1990–92 National Comorbidity Survey (US) reports that 51% of those with major depression also suffer from lifetime anxiety.[18] Anxiety

symptoms can have a major impact on the course of a depressive illness,

with delayed recovery, increased risk of relapse, greater disability

and increased suicide attempts.[19] American neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolskysimilarly argues that the relationship between stress, anxiety, and depression could be measured and demonstrated biologically.[20] There are increased rates of alcohol and drug abuse and particularly dependence,[21] and around a third of individuals diagnosed with ADHD develop comorbid depression.[22] Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression often co-occur.[6]

Depression and pain often

co-occur. One or more pain symptoms are present in 65% of depressed

patients, and anywhere from 5 to 85% of patients with pain will be

suffering from depression, depending on the setting; there is a lower

prevalence in general practice, and higher in specialty clinics. The

diagnosis of depression is often delayed or missed, and the outcome

worsens. The outcome can also worsen if the depression is noticed but

completely misunderstood.[23]

Depression is also associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease,

independent of other known risk factors, and is itself linked directly

or indirectly to risk factors such as smoking and obesity. People with

major depression are less likely to follow medical recommendations for

treating cardiovascular disorders, which further increases their risk.

In addition, cardiologists may not recognize underlying depression that

complicates a cardiovascular problem under their care.[24]

Causes

The biopsychosocial model proposes that biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role in causing depression.[25] The diathesis–

Depression may be directly caused by damage to the cerebellum as is seen in cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome.[29][30][31]

These interactive models have gained empirical support. For example, researchers in New Zealand took aprospective approach to studying depression, by documenting over time how depression emerged among an initially normal cohort of people. The researchers concluded that variation among the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene affects the chances that

people who have dealt with very stressful life events will go on to

experience depression. To be specific, depression may follow such

events, but seems more likely to appear in people with one or two short alleles of the 5-HTT gene.[26] In addition, a Swedish study estimated the heritability of

depression—the degree to which individual differences in occurrence are

associated with genetic differences—to be around 40% for women and 30%

for men,[32] and evolutionary psychologists have proposed that the genetic basis for depression lies deep in the history of naturally selected adaptations. A substance-induced mood disorderresembling major depression has been causally linked to long-term drug use or drug abuse, or to withdrawal from certain sedative and hypnotic drugs.[33][34]

Biological

Main article: Biology of depression

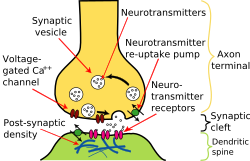

Monoamine hypothesis

Most antidepressant

Serotonin is

hypothesized to regulate other neurotransmitter systems; decreased

serotonin activity may allow these systems to act in unusual and erratic

ways.[35] According

to this "permissive hypothesis", depression arises when low serotonin

levels promote low levels of norepinephrine, another monoamine

neurotransmitter.[36] Some

antidepressants enhance the levels of norepinephrine directly, whereas

others raise the levels of dopamine, a third monoamine neurotransmitter.

These observations gave rise to the monoamine hypothesis of

depression. In its contemporary formulation, the monoamine hypothesis

postulates that a deficiency of certain neurotransmitters is responsible

for the corresponding features of depression: "Norepinephrine may be

related to alertness and energy as well as anxiety, attention, and

interest in life; [lack of] serotonin to anxiety, obsessions, and

compulsions; and dopamine to attention, motivation, pleasure, and

reward, as well as interest in life."[37] The

proponents of this theory recommend the choice of an antidepressant

with mechanism of action that impacts the most prominent symptoms.

Anxious and irritable patients should be treated with SSRIs or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and those experiencing a loss of energy and enjoyment of life with norepinephrine- and dopamine-enhancing drugs.[37]

Besides the clinical

observations that drugs that increase the amount of available monoamines

are effective antidepressants, recent advances in psychiatric genetics indicate that phenotypic variation in

central monoamine function may be marginally associated with

vulnerability to depression. Despite these findings, the cause of

depression is not simply monoamine deficiency.[38] In

the past two decades, research has revealed multiple limitations of the

monoamine hypothesis, and its explanatory inadequacy has been

highlighted within the psychiatric community.[39] A

counterargument is that the mood-enhancing effect of MAO inhibitors and

SSRIs takes weeks of treatment to develop, even though the boost in

available monoamines occurs within hours. Another counterargument is

based on experiments with pharmacological agents that cause depletion of

monoamines; while deliberate reduction in the concentration of

centrally available monoamines may slightly lower the mood of

unmedicated depressed patients, this reduction does not affect the mood

of healthy people.[38] The

monoamine hypothesis, already limited, has been further oversimplified

when presented to the general public as a mass marketing tool, usually

phrased as a "chemical imbalance".[40]

In 2003 a gene-environment interaction (GxE)

was hypothesized to explain why life stress is a predictor for

depressive episodes in some individuals, but not in others, depending on

an allelic variation of the serotonin-transporter-linked promoter

region (5-HTTLPR);[41] a 2009 meta-analysis showed

stressful life events were associated with depression, but found no

evidence for an association with the 5-HTTLPR genotype.[42] Another 2009 meta-analysis agreed with the latter finding.[43] A

2010 review of studies in this area found a systematic relationship

between the method used to assess environmental adversity and the

results of the studies; this review also found that both 2009

meta-analyses were significantly biased toward negative studies, which

used self-report measures of adversity.[44]

Other hypotheses

MRI scans

of patients with depression have revealed a number of differences in

brain structure compared to those who are not depressed. Recent

meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies in major depression, reported that

compared to controls, depressed patients had increased volume of the lateral ventricles and adrenal gland and smaller volumes of the basal ganglia, thalamus, hippocampus

There may be a link between depression and neurogenesis of the hippocampus,[48] a

center for both mood and memory. Loss of hippocampal neurons is found

in some depressed individuals and correlates with impaired memory and

dysthymic mood. Drugs may increase serotonin levels in the brain,

stimulating neurogenesis and thus increasing the total mass of the

hippocampus. This increase may help to restore mood and memory.[49][50] Similar relationships have been observed between depression and an area of the anterior cingulate cortex implicated in the modulation of emotional behavior.[51] One of the neurotrophins responsible for neurogenesis is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

The level of BDNF in the blood plasma of depressed subjects is

drastically reduced (more than threefold) as compared to the norm.

Antidepressant treatment increases the blood level of BDNF. Although

decreased plasma BDNF levels have been found in many other disorders,

there is some evidence that BDNF is involved in the cause of depression

and the mechanism of action of antidepressants.[52]

There is some evidence that major depression may be caused in part by an overactive hypothalamic-

The hormone estrogen has

been implicated in depressive disorders due to the increase in risk of

depressive episodes after puberty, the antenatal period, and reduced

rates after menopause.[54] On the converse, the premenstrual and postpartum periods of low estrogen levels are also associated with increased risk.[54] Sudden

withdrawal of, fluctuations in or periods of sustained low levels of

estrogen have been linked to significant mood lowering. Clinical

recovery from depression postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause

was shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized or

restored.[55][56]

Other research has explored potential roles of molecules necessary for overall cellular functioning:

Finally, some

relationships have been reported between specific subtypes of depression

and climatic conditions. Thus, the incidence of psychotic depression

has been found to increase when the barometric pressure is low, while

the incidence of melancholic depression has been found to increase when

the temperature and/or sunlight are low.[60]

Inflammatory processes

can be triggered by negative cognitions or their consequences, such as

stress, violence, or deprivation. Thus, negative cognitions can cause

inflammation that can, in turn, lead to depression.[61]

Psychological

Various aspects of personality and its development appear to be integral to the occurrence and persistence of depression,[62] with negative emotionality as a common precursor.[63] Although

depressive episodes are strongly correlated with adverse events, a

person's characteristic style of coping may be correlated with his or

her resilience.[64] In addition, low self-esteem and

self-defeating or distorted thinking are related to depression.

Depression is less likely to occur, as well as quicker to remit, among

those who are religious.[65][66][67] It

is not always clear which factors are causes and which are effects of

depression; however, depressed persons that are able to reflect upon and

challenge their thinking patterns often show improved mood and

self-esteem.[68]

American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck, following on from the earlier work of George Kelly and Albert Ellis,

developed what is now known as a cognitive model of depression in the

early 1960s. He proposed that three concepts underlie depression: a triad of

negative thoughts composed of cognitive errors about oneself, one's

world, and one's future; recurrent patterns of depressive thinking, or schemas; and distorted information processing.[69] From these principles, he developed the structured technique of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).[70] According to American psychologist Martin Seligman, depression in humans is similar to learned helplessness in

laboratory animals, who remain in unpleasant situations when they are

able to escape, but do not because they initially learned they had no

control.[71]

Attachment theory, which was developed by English psychiatrist John Bowlby in

the 1960s, predicts a relationship between depressive disorder in

adulthood and the quality of the earlier bond between the infant and the

adult caregiver. In particular, it is thought that "the experiences of

early loss, separation and rejection by the parent or caregiver

(conveying the message that the child is unlovable) may all lead to

insecure internal working models ... Internal cognitive representations

of the self as unlovable and of attachment figures as unloving [or]

untrustworthy would be consistent with parts of Beck's cognitive triad".[72] While

a wide variety of studies has upheld the basic tenets of attachment

theory, research has been inconclusive as to whether self-reported early

attachment and later depression are demonstrably related.[72]

Depressed individuals often blame themselves for negative events,[73] and,

as shown in a 1993 study of hospitalized adolescents with self-reported

depression, those who blame themselves for negative occurrences may not

take credit for positive outcomes.[74] This tendency is characteristic of a depressive attributional, or pessimistic explanatory style.[73] According to Albert Bandura, a Canadian social psychologist associated withsocial cognitive theory,

depressed individuals have negative beliefs about themselves, based on

experiences of failure, observing the failure of social models, a lack

of social persuasion that they can succeed, and their own somatic and

emotional states including tension and stress. These influences may

result in a negative self-conceptand a lack of self-efficacy; that is, they do not believe they can influence events or achieve personal goals.[75][76]

An examination of

depression in women indicates that vulnerability factors—such as early

maternal loss, lack of a confiding relationship, responsibility for the

care of several young children at home, and unemployment—can interact

with life stressors to increase the risk of depression.[77] For

older adults, the factors are often health problems, changes in

relationships with a spouse or adult children due to the transition to

a care-giving or

care-needing role, the death of a significant other, or a change in the

availability or quality of social relationships with older friends

because of their own health-related life changes.[78]

The understanding of depression has also received contributions from the psychoanalytic and humanis

Social

Poverty and social isolation are associated with increased risk of mental health problems in general.[62] Child abuse (physical, emotional, se

The relationship between stressful life events and social support has

been a matter of some debate; the lack of social support may increase

the likelihood that life stress will lead to depression, or the absence

of social support may constitute a form of strain that leads to

depression directly.[91] There

is evidence that neighborhood social disorder, for example, due to

crime or illicit drugs, is a risk factor, and that a high neighborhood

socioeconomic status, with better amenities, is a protective factor.[92] Adverse

conditions at work, particularly demanding jobs with little scope for

decision-making, are associated with depression, although diversity and

confounding factors make it difficult to confirm that the relationship

is causal.[93]

Depression can be caused

by prejudice. This can occur when people hold negative self-stereotypes

about themselves. This "deprejudice" can be related to a group

membership (e.g., Me-Gay-Bad) or not (Me-Bad). If someone has

prejudicial beliefs about a stigmatized group and then becomes a member

of that group, they may internalize their prejudice and develop

depression. For example, a boy growing up in the United States may learn

the negative stereotype that gay men are immoral. When he grows up and

realizes he is gay, he may direct this prejudice inward on himself and

become depressed. People may also show prejudice internalization through

self-stereotyping because of negative childhood experiences such as

verbal and physical abuse.[61]

Evolutionary

Main article: Evolutionary approaches to depression

From the standpoint of evolutionary theory, major depression is hypothesized, in some instances, to increase an individual's reproductive fitn

[Message clipped] View entire message

|

Jul 16 (2 days ago)

| |||

| ||||

What are your disorders?

|

Click here to Reply or Forward

|

Why this ad?Ads –

room Thai style at School Accredited by Ministry of Education

1.15 GB (7%) of 15 GB used

©2014 Google - Terms & Privacy

Last account activity: 40 minutes ago

Details

No comments:

Post a Comment